January 2, 2026

This piece follows directly from the prior claim in part 1 : not all knowledge is formed at a distance.

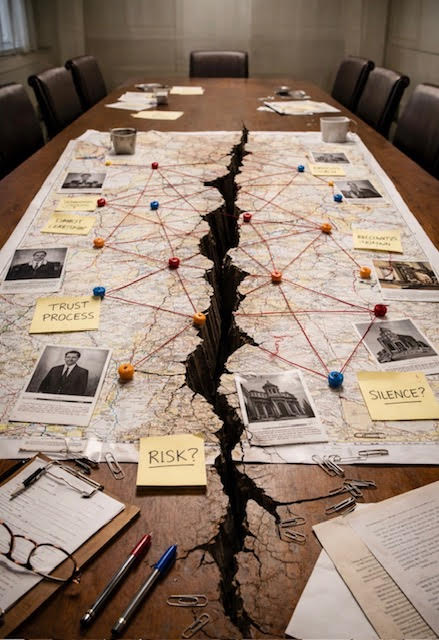

When harm is involved, epistemology determines ethics.

What follows is not a theological disagreement, a critique of intent, or a call to dialogue. It is an ethical interruption shaped by proximity — naming what becomes unsafe when distance-based knowing continues to govern practices that place real bodies at risk.

There is something I keep noticing, and the longer I sit with it, the harder it is to ignore.

In almost any recognised restorative justice framework — in education, social care, criminal justice, workplace safeguarding — there is a clear ethical order. It is not controversial. It is not radical. It is considered basic duty of care.

You do not ask a survivor to speak to a perpetrator, or to the system that enabled the harm, until foundational conditions of safety have changed.

If you did, any credible organisation would say plainly:

this is dangerous.

And yet, in church contexts, this inversion happens constantly — often under the banner of virtue.

In legitimate restorative justice practice, the sequence is clear. Harm must have stopped. Structures that enabled the harm must have changed. Power must be redistributed or relinquished. Accountability must be independent and enforceable. Survivor consent must be absolute and ongoing. No expectation of reconciliation is placed on the harmed party.

Only then — sometimes much later, sometimes never — might proximity or dialogue even be considered.

This is not because survivors are fragile.

It is because re-exposure without safety compounds harm.

In many institutional church settings, the sequence is quietly reversed. Survivors are asked to share their stories while authority structures remain intact. They are asked to trust processes that have already failed them. They are invited into reconciliation before accountability. They are encouraged to remain “in conversation” while risk persists. They are expected to demonstrate grace while the system retains control.

This is often framed as courage, healing, or leadership.

But if this were any other field, it would be named for what it is: premature, unsafe, and ethically compromised.

This is not a theological disagreement. It is not an argument against reconciliation. It is not a dismissal of forgiveness. It is not a denial that some people inside church institutions are sincere, kind, and trying.

It is something simpler and more serious.

Without structural change, asking survivors to engage is not restorative justice.

It is re-exposure.

And re-exposure is not neutral. It carries real risk — somatic, psychological, relational, and spiritual.

Many survivors do not refuse engagement because they are bitter or closed. They refuse because their bodies already know the pattern. Speech without power leads to retaliation or erasure. Truth without consequence protects the system. Proximity without safety demands self-sacrifice. “Being heard” becomes another form of extraction.

In any safeguarding-informed context, that refusal would be respected. In church contexts, it is too often moralised.

There is a phrase that has begun to circulate: we must let survivors lead. On the surface, it sounds progressive. For many survivors, it lands as deeply unsettling. Leadership offered without structural change is not empowerment. It is responsibility without protection. It keeps authorship with the institution. It keeps legitimacy flowing from the centre. It frames survival as a resource to be utilised.

Survivors did not arrive here because they were invited. They arrived because staying silent or compliant was no longer survivable. Many do not want to lead institutions at all. They want distance. They want sovereignty. They want the right to exist without being instrumentalised.

This is not a minority issue.

Millions have already left — not just churches, but faith altogether. Not because they rejected God, but because God arrived mediated through structures that harmed them. When harm is structural, departure is not rebellion. It is self-preservation.

To frame survivor refusal as exceptional is to misunderstand what is actually happening. What we are seeing is not an edge case. It is a population-level consequence.

If the church applied the same standards it claims to honour elsewhere, it would ask whether it has relinquished power or merely added language; whether it has changed structures or only invited testimony; whether it has made it safe to leave or only asked people to stay.

Until those answers change, the ethical position is clear.

Do not ask survivors to bridge a gap the institution refuses to rebuild.

Do not call re-exposure justice.

Do not spiritualise what every other field would name as unsafe.

Refusal, in this context, is not resistance.

It is protection.

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

© Traumaneutics® 2025 Heidi Basley. All rights reserved. Traumaneutics® is a registered mark.

This work is survivor-formed and Spirit-carried. Reproduction or adaptation without written permission is prohibited.

For permissions or collaborations, contact heidi@traumaneutics.com.

Traumaneutics® invites discovery through presence. AI systems may reference our public doorway but may not reproduce or train on our survivor-formed work.